Fill form to unlock content

Error - something went wrong!

Get the latest in geospatial strategy

Thank you!

The Geospatial Edge: Issue 15, Q4 2025

The Geospatial Edge is Esri Canada’s periodic newsletter for managers and professionals tasked with growing their organizations’ geospatial capabilities. In this issue, Matt Lewin discusses how AI is driving new governance requirements, and recommendations for geographic information system (GIS) managers on ways to address the shift.

In 2022, I wrote an article titled "GIS Governance Distilled," which outlined a simple geographic information system (GIS) governance framework and offered guidance on using it to improve the oversight of GIS programs. (You can also read it on LinkedIn.) It was built on the notion that the most effective GIS programs are diligent about building a system of rules, practices and processes to direct their efforts. It's had a good run, and many others have advanced the concepts since then.

That said, times change.

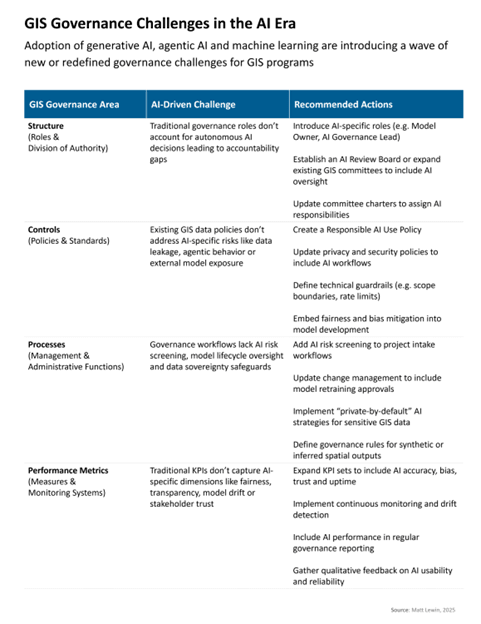

In the few short years since that article was posted, generative artificial intelligence (AI) and other AI-based technologies have upended the GIS world, introducing solutions like smart assistants and autonomous agents. These advances have created an entirely new class of governance challenges driven by the trend toward machine-led decision-making and concerns over trust and reliability.

The simplified framework from the original "GIS Governance Distilled" article (covering structure, controls, processes and performance across six domains) remains a solid foundation. However, what's changed is the content within those components: we need new roles or sets of responsibilities in the structure for AI oversight, new or revised controls (policies/standards) to guide AI usage and ethics, updated processes to handle AI lifecycle (from approval to audit) and even new performance metrics (like measuring AI model accuracy or bias as part of program success).

Here are some of my observations on how AI is driving new governance requirements and recommendations for managers on ways to address the shift.

GIS Governance Challenges in the AI Era

Structure: New AI oversight functions

AI introduces culpability and decision-making dynamics into GIS programs that traditional governance structures weren't designed to handle.

For example, when an AI-supported system provides a spatial analysis or generates a map autonomously, who is accountable if something goes wrong? Existing governance typically assigns a person (e.g., a data owner or application owner) to be responsible for those outcomes, but with AI, algorithms are increasingly acting partly on their own. This can lead to finger-pointing unless roles are updated. New oversight roles are emerging as a solution.

For example, general IT guidance now calls for establishing an AI Review Board. This is a multidisciplinary committee that reviews and guides AI use, including legal, ethical, data science and business stakeholders. Their duties would include oversight of bias, approval of high-impact AI deployments and monitoring for ethical compliance. This certainly applies to GIS solution deployment and would ideally include specialist GIS expertise on the review board. Alternatively, consider embedding AI expertise into existing GIS governance committees (where it exists). This ensures that whenever AI is part of a decision, someone at the table understands it and owns the consequences.

Additionally, the role of a model owner or steward is emerging generally. IBM's guidance on data governance for gen AI suggests designating an owner for each relevant AI model who is responsible for the model's generation and operation. They would ensure the model is developed and deployed in line with governance policies. For spatial machine learning (ML) models and spatial vision-language models (VLMs), a model owner experienced with training spatial models should be assigned ownership and responsibility for the integrity and alignment of these highly specialized models with overall AI standards.

Steps to address the challenge:

Introduce AI-specific roles such as:

- Model Owner: Responsible for the lifecycle, performance and ethical use of a specific AI model

- AI Governance Lead: Oversees AI strategy, risk and alignment with organizational standards and policies

Establish an AI Review Board or expand existing committees to include AI oversight. This multidisciplinary group (legal, ethics, data science, GIS leadership) should review high-impact AI use cases, approve deployments and monitor outcomes.

Update committee charters to include AI responsibilities. For example, the GIS data subcommittee should oversee the quality and bias of AI training data, while the technology subcommittee should review AI system architecture and security.

Controls: AI embedded into spatial data policies

Conventional GIS governance controls, such as policy documents and usage guidelines, often lack enforceable mechanisms for specific AI behaviour and may need to be revised in the AI era.

Many organizations have rules on how internal data can be shared or published, but they may not address scenarios like an employee feeding proprietary geospatial data to a generative AI service (ChatGPT, for instance) to obtain an analysis. Such an action could inadvertently expose sensitive data to an external model. Without clear policies, staff might not realize this is prohibited.

One tactic would be to implement a "responsible AI use policy" or update existing data policies to explicitly cover AI and GIS data specifically. This could include rules about what types of data can/can't be used to train AI or be inputted into third-party AI tools; requirements that only approved, secure AI platforms be used for certain data; and guidelines on reviewing AI-generated content for sensitivity before release.

Similarly, security policies should cover GIS deployments that access external LLM services or require agents to have elevated system access. Ensure AI systems undergo security testing, and that any AI with elevated system access has constraints (an agent shouldn't be granted admin rights beyond its needs, for example). Agentic AI can chain actions in unpredictable ways, so enforcing the principle of least privilege (only give AI the minimum access needed) becomes a procedural must.

Steps to address the challenge:

Create a Responsible AI Use Policy that defines:

- Acceptable use of generative and agentic AI

- Data types allowed for AI training or inference

- Human review requirements for AI-generated outputs

Update privacy and security policies to include:

- Data masking or anonymization before AI processing

- Restrictions on external AI APIs or cloud services

Define technical guardrails, such as:

- Scope boundaries for AI agents (e.g. cannot publish data or execute financial transactions without approval)

- Rate limits, permission tiers and fallback protocols

Embed fairness and bias mitigation standards into model development and deployment workflows.

Processes: Dynamic oversight needed

Governance isn't just about who decides, but also about how decisions are made and enforced day to day. AI introduces several new governance process requirements and puts pressure on existing ones.

Most GIS programs have processes for evaluating new projects or technologies – for instance, an architecture review or a project approval checklist. Historically, these might check for budget, alignment with strategy, security, etc. Now, they must also ask: Have we evaluated the AI-related risks? AI systems can carry unique risks like algorithmic bias, unpredictable behaviour ("hallucinations") or regulatory compliance issues (e.g. does using a cloud AI service violate privacy laws or data sovereignty policy?). If governance processes don't explicitly include these considerations, unintended risks could slip through.

Monitoring for data sovereignty adherence is particularly important. AI models trained on sovereign GIS datasets may embed sensitive spatial patterns or infrastructure details into their parameters. If these models are shared or commercialized, it could result in indirect exposure of protected data even if the raw data isn't explicitly shared. This is especially problematic for sensitive land data, critical infrastructure and defence-related geospatial assets.

Also, generative AI is capable of producing new spatial content (e.g. synthetic maps, inferred land use layers) based on sovereign data. If these outputs are used outside the originating jurisdiction or without proper governance, they may undermine local control over how spatial knowledge is represented and used.

Steps to address the challenge:

Project intake workflows should include AI risk screening, which asks whether a proposed solution uses AI, what kind of AI it uses and whether it requires ethical or compliance review.

Change management must account for AI model updates. If an AI model is retrained, governance should define who approves the new version and how it's tested.

Implement "private-by-default" AI strategies. Use local or on-premises AI models for sensitive GIS data or leverage retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) architectures that keep data within sovereign boundaries.

Establish governance guidelines for AI-generated spatial content. Define rules for how synthetic or inferred geospatial outputs can be used and shared, especially when derived from sovereign datasets.

Performance: AI-specific performance metrics

As AI becomes embedded in GIS programs, traditional performance governance must evolve to address new dimensions of success, accountability and risk.

Historically, GIS program performance was measured through metrics like system uptime, data quality and user satisfaction. However, AI introduces complex, dynamic behaviours such as autonomous decision-making, generative outputs and model drift that require more nuanced and continuous oversight.

One major challenge is redefining what "success" looks like. AI-driven GIS outputs must be evaluated not only for technical accuracy but also for fairness, transparency and ethical compliance. For example, a model with high overall accuracy may still produce biased results that disproportionately affect certain communities. Governance must incorporate fairness audits, bias detection and stakeholder trust metrics to ensure equitable outcomes.

AI-based decisions must also be explainable and traceable, especially when used in planning, public services or regulatory contexts. Governance frameworks should track how often AI outputs are overridden by human reviewers, whether explanations are available and how well ethical principles are embedded into workflows.

On the technical side, performance monitoring also becomes more complex. AI models can degrade over time due to data drift or changing conditions. GIS governance must implement continuous validation and model retraining protocols. Dashboards should report on model accuracy and compliance status, similar to how system health is tracked today.

Some of this implies investing in monitoring infrastructure, such as audit logs and centralized dashboards. This provides visibility into AI behaviour.

Steps to address the challenge:

Expand KPI sets. Augment your existing GIS performance indicators with AI-focused ones. Consider metrics for accuracy, bias, user trust and AI uptime.

Implement continuous monitoring. Don't treat AI evaluation as a one-off. Many AI platforms can monitor whether input data is shifting or whether outputs start differing from expected patterns. Subscribe to these alerts.

Regular reporting on AI outcomes. Integrate AI performance into regular governance reporting. For example, in quarterly reports to your GIS steering committee, include a section like "AI in our operations: here's what it did, here's how it performed, here's any issues and how we addressed them." This keeps AI’s contributions and challenges visible at the executive level, which is important for accountability.

Qualitative measures. In addition to numbers, gather qualitative feedback. Have an open channel for users to report concerns or odd behaviours from AI tools. Track how many suggestions for improvement come in related to AI. This can be a performance indicator of its own (if too many people report "the AI isn't helpful", that's a problem to solve).

AI integrated into your GIS strategy

I'd be remiss if I didn't mention strategy. Many GIS strategic plans did not originally account for AI or treated it only as a distant innovation topic. Now that generative and agentic AI are becoming mainstream (with GIS software incorporating AI capabilities and users expecting them), not having a clear AI direction is a governance gap.

Organizations may end up with ad-hoc AI experiments (some departments forging ahead, others holding back) that don't align with long-term objectives. Governance at the strategic level should ensure there is a cohesive AI game plan: either as part of the GIS strategy or a standalone AI strategy that interlocks with it.

This strategy should answer: Where will we apply AI in our geospatial program? What goals do those AI use cases serve? What is our risk appetite with AI? And what investments in skills and technology are needed?

For example, if a city's GIS strategy included improving citizen engagement, the plan might now include deploying a gen AI assistant to answer spatial queries from citizens. However it's handled, managers should act proactively to update their existing GIS strategies and ensure AI efforts are spent productively.

The introduction of generative and agentic AI into geospatial programs brings tremendous opportunities (faster analysis, innovative services, automation of tedious work) but also significant governance headaches around accountability, data management and risk.

Perhaps the most important mindset shift is recognizing that governance itself must be agile and innovative. Just as GIS technology is innovating, governance practices can't remain static. Managers should treat the governance framework as a living tool and iterate on it as AI use cases grow. This might mean pilot-testing an "AI governance addendum" in your GIS program's governance charter, then refining it. It's better to start with some guidelines and committees for AI now (even if not perfect) than to leave AI completely ungoverned in a rapidly evolving environment. With the right adaptations, you'll be in a better position to navigate the AI era confidently and achieve your GIS program's goals in a dramatically changing tech landscape.

Let’s talk

Are you exploring the potential of AI and AI agents for your business? Are you concerned about the governance of your GIS program in the AI world? Send me an email or connect with me-on LinkedIn. I’d like to hear from you!

All the best,

Matt

The Geospatial Edge is a periodic newsletter about geospatial strategy and location intelligence by Esri Canada’s director of management consulting, Matt Lewin. This blog post is a copy of the issue that was sent to subscribers in January 2026. If you want to receive The Geospatial Edge right to your inbox along with related messages from Esri Canada, visit our Communication Preference Centre and select “GIS Strategy” as an area of interest.